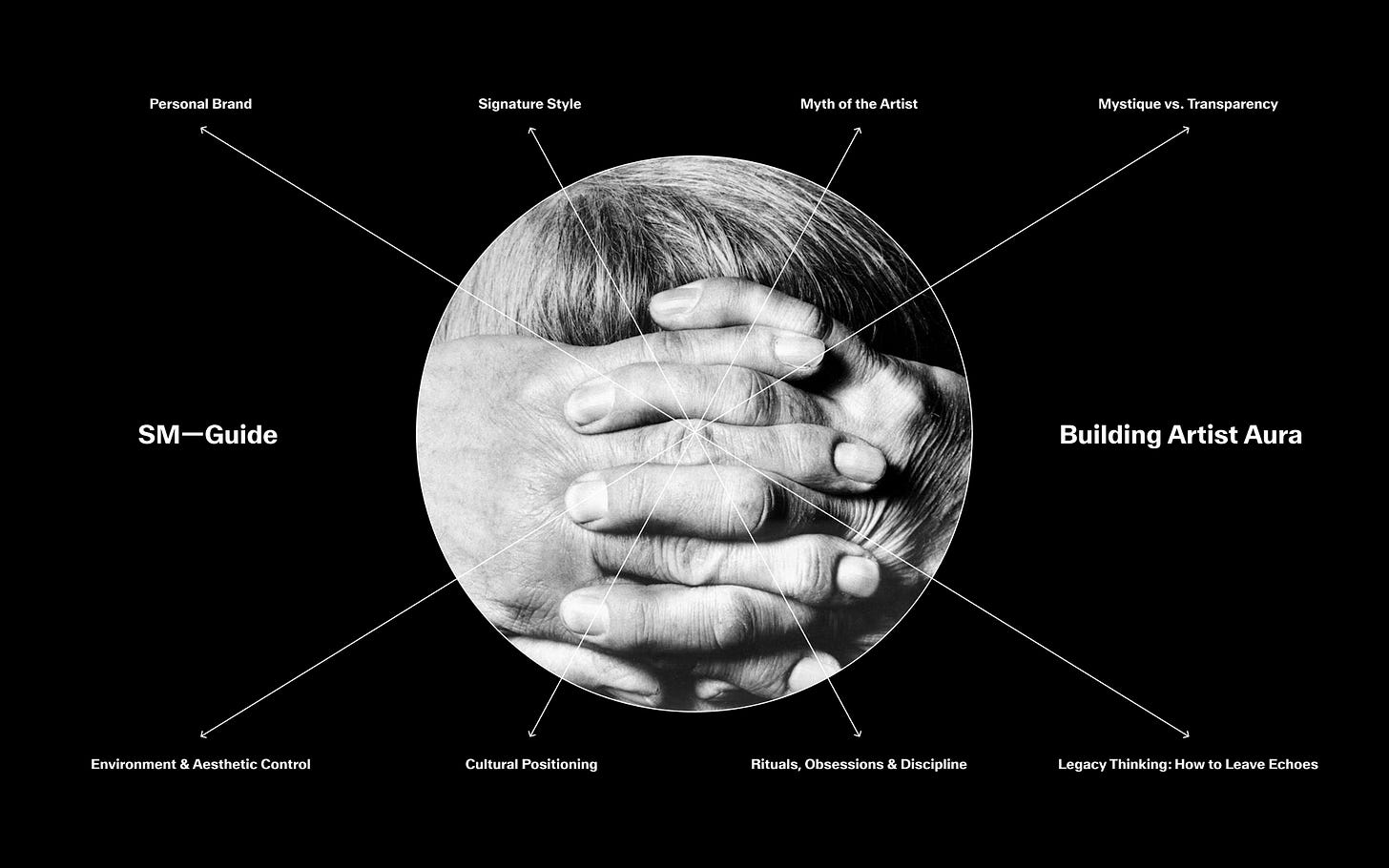

SM—Guide: Building Artist Aura | Part II

A Guide to Building a Creative Following in the Modern Age

Welcome to the SM—Guide: a space where we slow things down a bit. Think less trend report, more creative field manual for the modern age. Each episode is a deep dive into the ideas, strategies, and undercurrents changing the way the creative class operates today. Whether you're an artist, designer, or somewhere in between, this series will begin to unpack what actually matters when building a contemporary creative practice today. Follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn for more content and consider becoming a paid subscriber to Social Medium to receive full access to our platforms.

Before we start, if you are here and haven’t read Part I, we recommend stopping and giving that a read first (and give it a like while your at it!). If you’ve read it and are coming back for Part II – then let’s begin ✈️

When we wrote Part I of this guide, we were thinking about presence — that sense of creative gravity that makes a person feel instantly significant, even if you can’t explain why. We were tracing outlines. Studying how artists build personal brands and visual languages so strong that they can be felt before they’re understood. It was about getting seen.

But visibility isn’t the whole story, and lately — maybe because we’re both a little older, or a little more disillusioned with the algorithmic churn — we’ve been thinking less about being seen, and more about being remembered.

So what actually sticks? What gives a body of work that slow-burning cultural half-life, the kind that deepens over time instead of disappearing in a week?

That’s what this second part is about. Not the glow-up, but the afterglow.

The more time we’ve spent studying the artists we admire — from the fashion ghosts to the folk prophets to the barely-Googlable weirdos in museum basements — the more we’ve noticed: longevity isn’t just about style, it’s about myth. It’s about mystique. It’s about what you choose to withhold as much as what you share.

Some artists disappear in order to be seen more clearly. Some reinvent themselves until there’s no version left to hold onto. Some give everything away, but frame it so carefully it still feels sacred. These are the artists who don’t just make work — they invent legends. And that’s where we’re heading in Part II.

This chapter is about the deeper narratives that support a lasting aura — how myth builds weight around a name, and how mystery can be just as powerful as exposure. We’ll look at artists who chose to vanish (Martin Margiela), those who chose to shapeshift (Bob Dylan), and those who’ve redefined transparency and mystique in a world that’s increasingly hostile to both (Virgil Abloh and Kai Althoff).

Because in a culture obsessed with visibility, there’s real power in learning how to disappear — or at least in knowing when not to speak. So let’s begin…

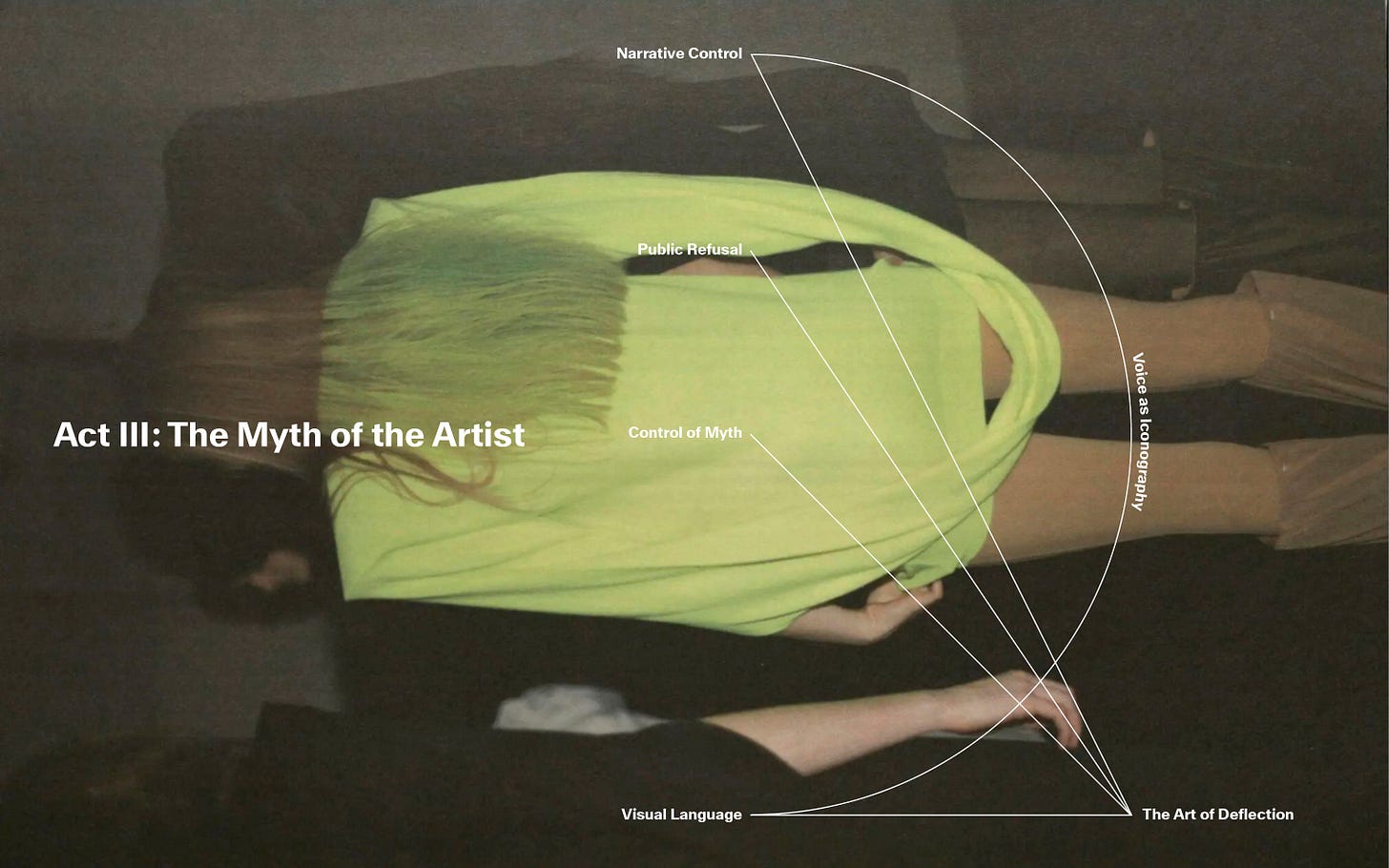

Act III: The Myth of the Artist

A Case Study: Martin Margiela

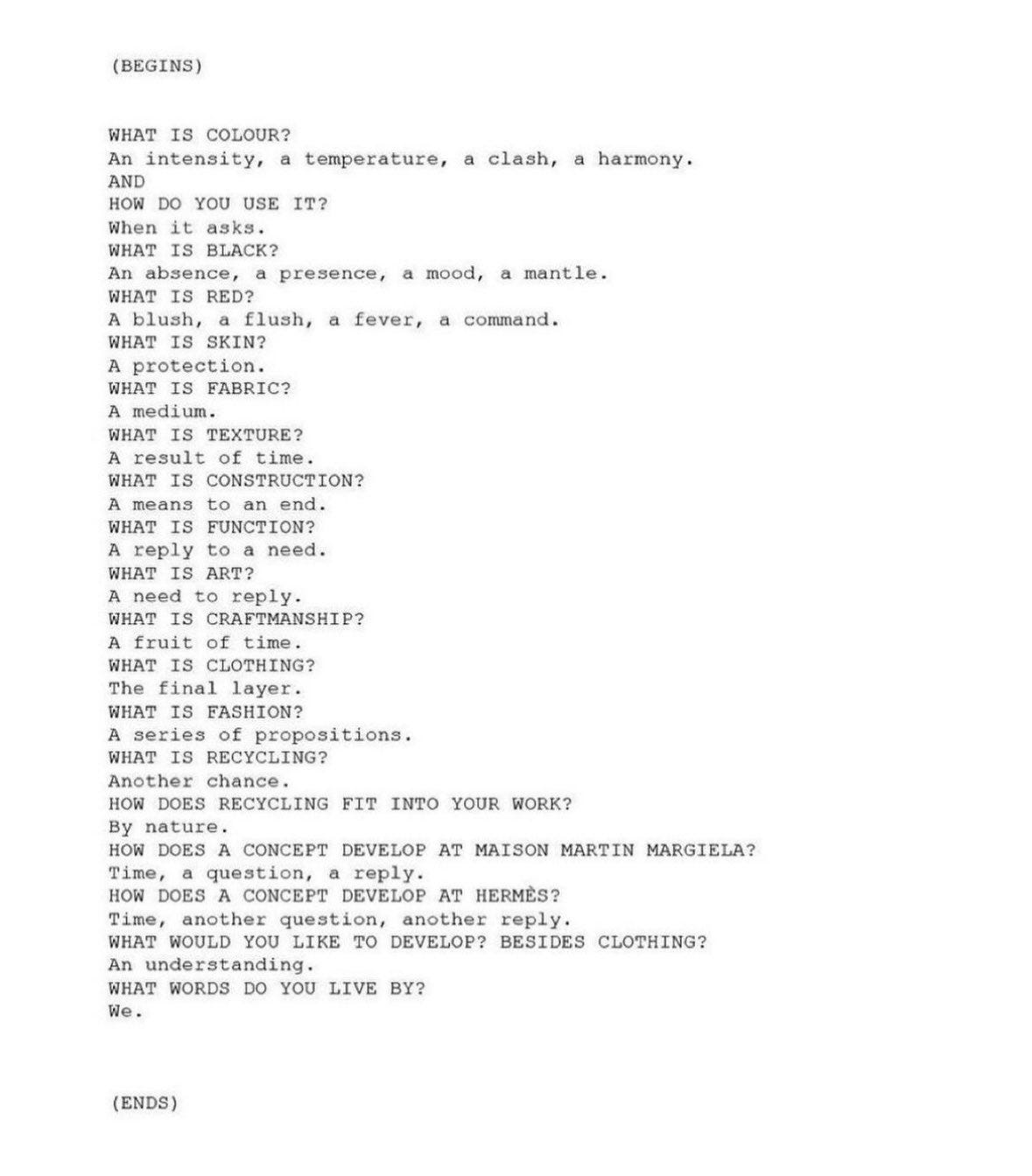

When we talk about “artist aura,” we usually mean charisma. Some blend of presence, performance, and public mythology. However, Martin Margiela built a legacy by disappearing from his own narrative.

He refused interviews. Never posed for a photo. Didn’t take a bow after runway shows. And yet (or maybe because of that) he became one of the most mythologised and influential designers of the modern era. While most designers were building cults of personality, Margiela erased himself entirely, letting the work speak on its own terms. And in doing so, he created a new kind of authorship. One defined not by visibility, but by presence.

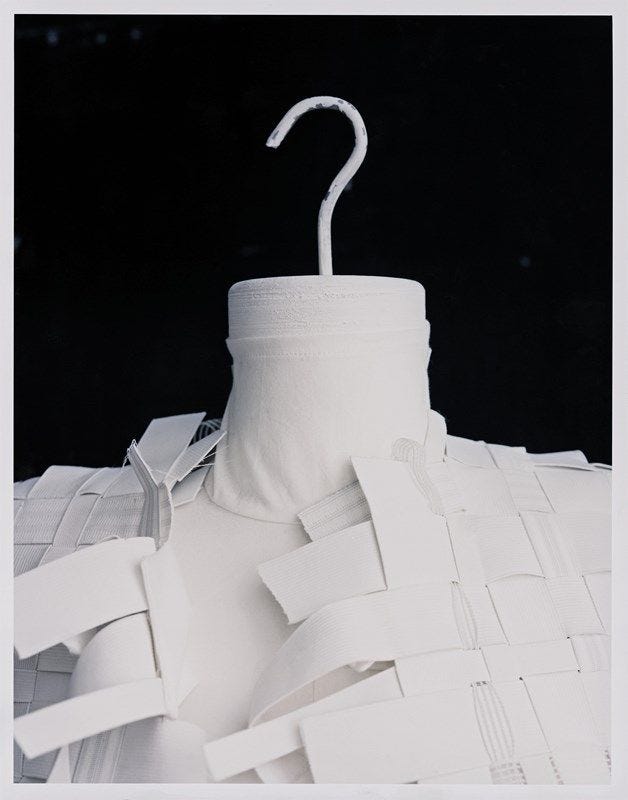

Visual Language

Martin Margiela didn’t whisper about construction, he made it super loud within his process. Every seam, raw edge, and cutaway lining in his garments told you where the garment came from and what it used to be. Fashion, at the time, was obsessed with illusion — the trick of making something look effortless. Margiela instead dragged the mechanics into the light, dipping shoes in paint, dresses were made from old gloves and blazers bore the inside label turned outward. He made visible the things fashion was built to hide. And in doing so, he carved a new grammar into the fabric of the industry.

His pieces were less about silhouette and more about suggestion. A jacket wasn’t just a jacket, it was a map of how a jacket is made. A pair of boots, dipped in white paint, left trails on the runway. His designs hinted at previous lives. They felt lived-in and like found objects. And while it could’ve come off as gimmick, it never did.

But even more striking than the work itself was how it was presented. Runways shows were held in abandoned metro stations, models walked the runway with faces obscured by hair or cloth. Invites were faxed instead of mailed. The shows didn’t feel like fashion events. They felt like happenings. Temporary spaces where fashion and performance art blurred.

He rejected the industry’s obsession with polish, perfection, and by stripping away the visual cues of status, Margiela made space for something else: intimacy. Attention to detail. A sense of being in on something that didn’t need to shout to be heard.

Public Refusal

Margiela’s refusal to participate in the fame economy wasn’t some marketing stunt — it was the core of his philosophy. He knew that mystery could be more powerful than personality. He never appeared at the end of a show. Interviews were conducted via fax machine often referring to a collective “we” versus “I”. There are barely any confirmed photographs of him. And even his design team, at Maison Martin Margiela, operated collectively, and often anonymously.

And despite how it may be perceived, he wasn’t shy or awkward, rather he was building something that couldn’t be diluted by public image. The more he receded, the more we projected. The less he said, the more was said about him. He turned silence into a signal and it created Margiela mythology.

In a culture addicted to access and personal branding, Margiela offered nothing — and in doing so, became everything. His absence didn’t create emptiness. It created myth.

Control of Myth

The most subversive thing Margiela ever did wasn’t making a dress made of wigs or a dipping a boot in paint. It was letting go of authorship. His garments invited you to participate, to see yourself in them, or to lose yourself in the story. They didn’t come with commentary or explanation. They asked you to fill in the blanks and to find your own meaning in the fragments.

When he walked away in 2009, there was no farewell, he just disappeared, and the world kept talking about him. That final act — a total, wordless exit — baked in the myth. His career became a kind of art installation in itself, a decade-long performance piece about what it means to truly disappear without ever being forgotten.

Since then, retrospectives, documentaries, and entire cult followings have tried to trace the outline of his influence. But the truth is, the absence is part of the design. Margiela teaches us that the artist doesn’t need to be visible to be felt. That silence, when intentional, can say more than a thousand interviews. And that in a world addicted to exposure, pulling back can be the most radical gesture of all.

So what’s the takeaway?

Margiela teaches us that visibility is not a requirement for influence. That mystique can be crafted not through spectacle, but through absence. That silence, when intentional, becomes a kind of authorship in itself. He proves that the artist doesn’t have to perform to make powerful work. That aura doesn’t always come from more but sometimes it comes from less.

And in a culture where everything is documented, shared, branded, and optimised for engagement, the decision to pull back and not to participate is radical. Margiela didn’t just create clothes. He created a myth. And that myth wasn’t built through exposure. It was built through absence.

A Case Study: Bob Dylan

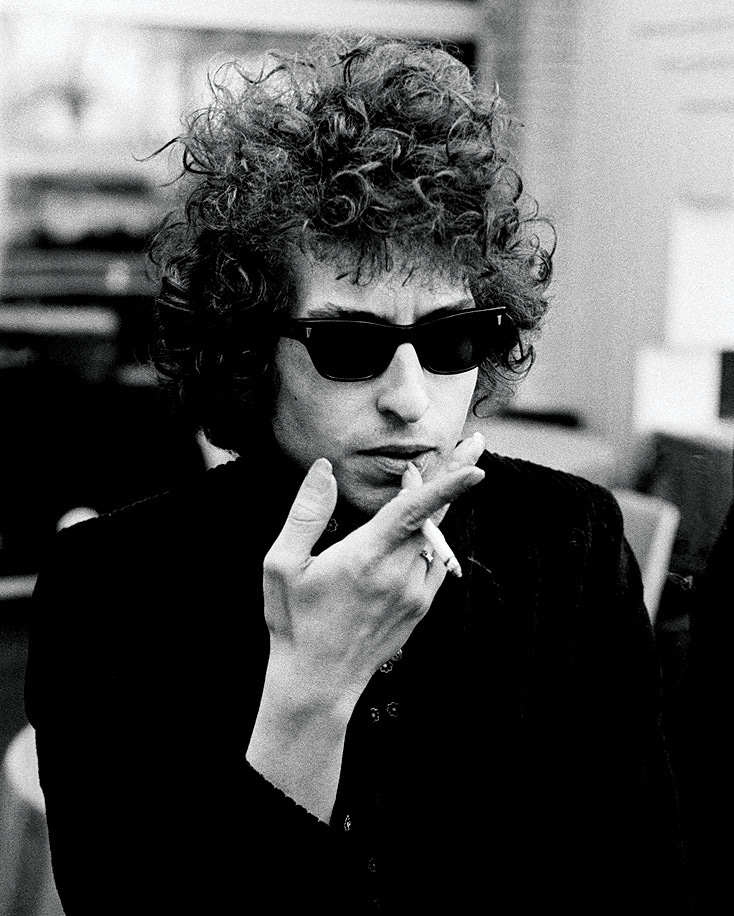

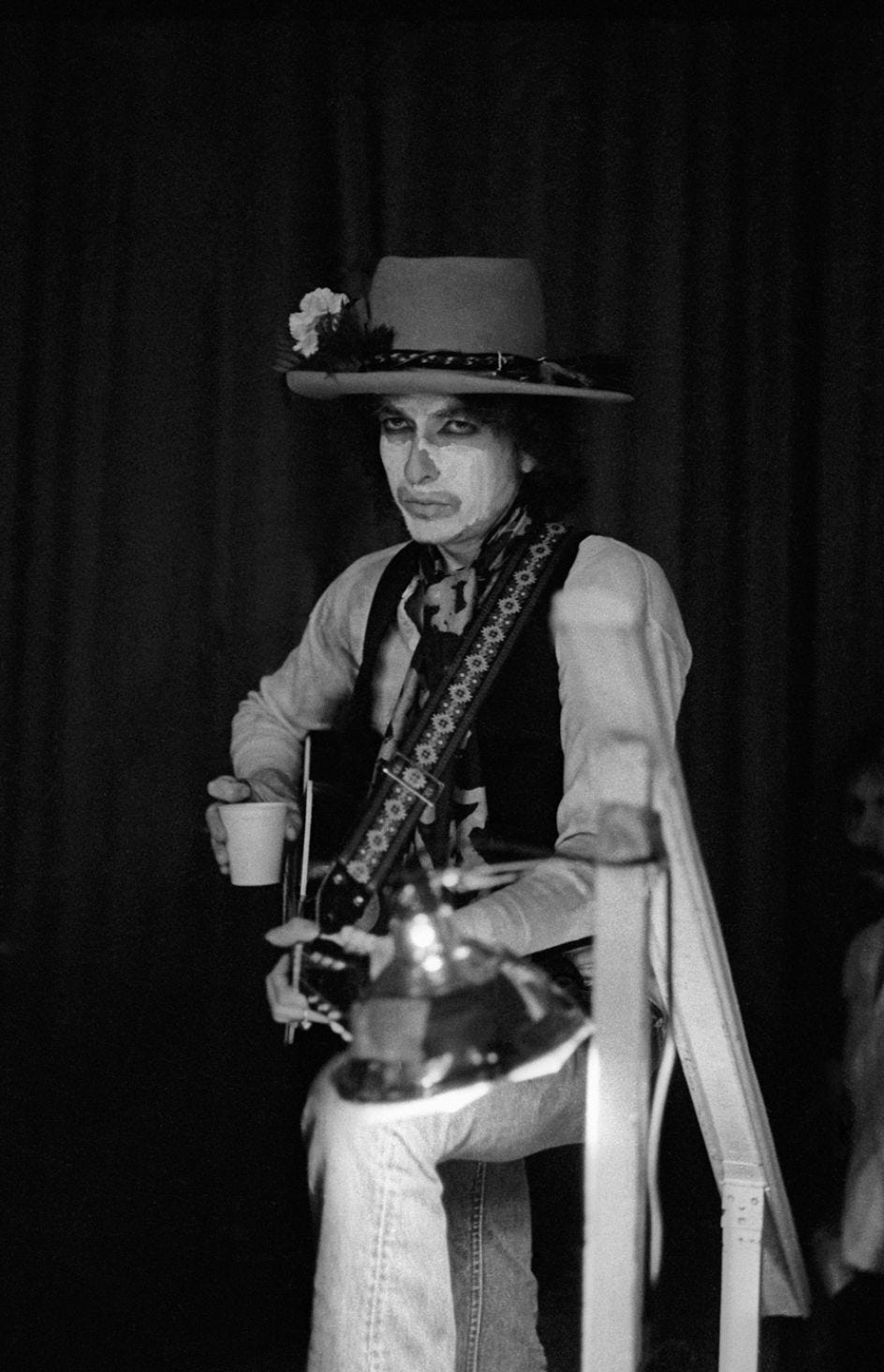

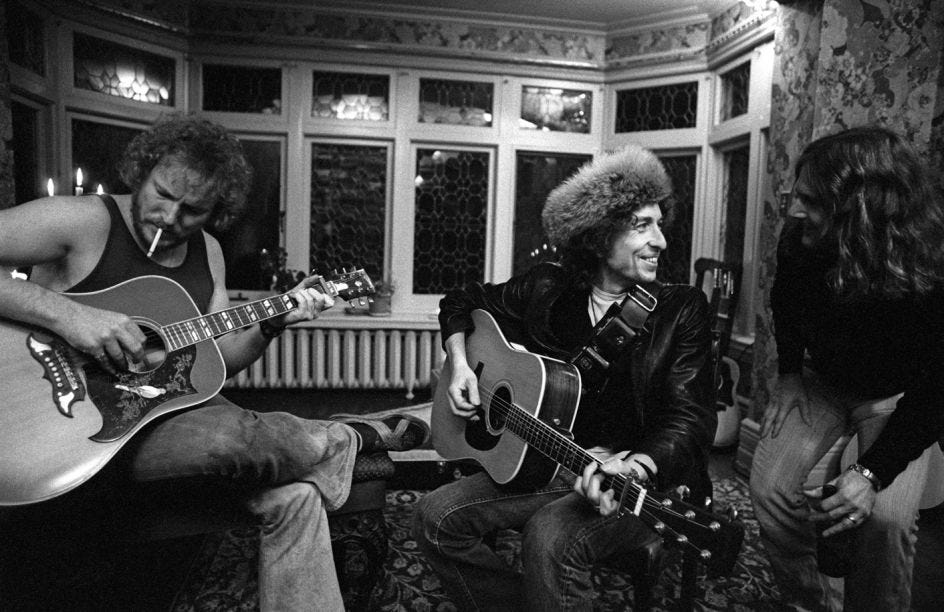

If Margiela built myth through erasure, Bob Dylan built his by being everywhere and yet always just out of reach. He was visible. Prolific. Ubiquitous. A cultural constant. And still, nobody could pin him down. Where Margiela vanished, Dylan multiplied again and again and again.

Folk poet. Electric trickster. Country crooner. Christian preacher. Each phase layered over the last, thickening the myth without ever resolving it. To the point that every version of him now feels equally real and equally out of reach. Dylan shows us that myth isn’t always about silence. Sometimes it’s about motion. About refusing to stay still long enough to be defined.

Narrative Control

From the beginning, Dylan understood that identity was a moving target. He didn’t give the public what they wanted , rather, he went against his fan base knowing that eventually they would catch up. He’d write up a protest anthem that would come to define a generation only to follow it with a surrealist love song. He became the symbol of modern folk music then would drop it and go electric, and once fans caught onto the brilliance he would then go veer into gospel. One tour he’d mumble through every hit, the next he’d reinvent his entire back catalogue with different tempos and chord structures.

But none of this was calculated marketing. It wasn’t even rebellion, really. It was instinct. Dylan didn’t seem interested in managing his image, rather he wanted to escape it. Singing lines like “The future for me is already a thing of the past…” his legend built itself because he never stopped moving. And that motion became a kind of authorship.

And it worked. The legend built itself because he never stood still. Each transformation wasn’t just a new style, it was a shedding of skin. A deliberate refusal to be confined by any single version of himself. Dylan understood that to be mythic, you have to be bigger than one narrative and slipperier than any single era.

Voice as Iconography

Most artists try to refine their voice into something beautiful and something consistent. Dylan did the opposite. His voice — nasally, ragged, off-key, and unconcerned with traditional beauty — became its own form of branding. It wasn’t designed for mass appeal. It was imperfect, idiosyncratic, and immediately recognisable. It shifted over time, mirroring his phases. There’s a version of his voice for every Dylan era, young and urgent, wry and snarling, weary and wise. It was built for recognition.

He didn’t try to sound like anyone else, and he didn’t try to please. And in doing so, he changed the rules and his delivery gave permission to generations of musicians to lean into their own rawness. To use the voice not just as a tool, but as a mirror of identity in flux.

The Art of Deflection

Dylan’s interviews are masterclasses in evasiveness. He sidesteps questions, delivers one-liners, invents backstories, and trolls reporters with deadpan seriousness. But what seems like cagey behaviour is really a refusal to be owned by the media. He knew that the more he explained himself, the more they could define him.

But this isn’t evasiveness for its own sake. It’s control. Dylan knew that explanation dilutes myth. The more he defined himself, the easier it would be for others to define him back — to box him in, make him digestible, reduce him to a tagline. And Dylan was never going to let that happen.

In 1965, a reporter asked if he saw himself as a singer or a poet. Dylan famously replied, "I think of myself more as a song and dance man." That kind of pivot kept him in control. He understood that ambiguity is a form of authorship. He didn’t want to be a prophet, a spokesperson, or a poet. He wanted to keep the frame loose. And in doing so, he gave himself the space to evolve.

A Living Archive

What makes Dylan’s myth so powerful is that it isn’t frozen, it’s still happening today. Albums continue to emerge, tour dates appear and bootlegs surface in record stores. Every version of him is somehow still present — the young rebel, the tired prophet, the inscrutable oracle. Each era writes over the last without erasing it. Building and building.

His story isn’t a brand. It’s a body of work and he lets the art carry the myth forward, and leaves you to make sense of it. And everybody does.

So what’s the takeaway?

Dylan shows us that myth doesn’t have to be built through silence or withdrawal. It can be built through motion. Through reinvention. Through refusing to settle on a single version of yourself.

Where Margiela reduced visibility to amplify presence, Dylan multiplied to stay just out of reach. Both understood the same thing: that aura isn’t about access — it’s about distance. It’s about the gap between what people see and what they understand. And that’s where myth lives.

Dylan’s refusal to stand still is what kept him in control. He didn’t disappear. He just kept moving faster than the story could catch up.

Act IV: Mystique vs. Transparency

If the myth of the artist is about how you build meaning around yourself, mystique vs. transparency is about how much you choose to show once people start paying attention to you.

We’re in a moment where visibility is both a creative tool and, (sometimes sadly) a social expectation. Artists are asked to explain, engage, and document their lives and process. Some lean into it and make it part of the work, others resist it protecting their process like a sacred practice.

To explore this tension, we’re looking at two artists with completely different approaches: Virgil Abloh, who opened everything up, and Kai Althoff, who draws the curtain shut. One made his legacy by sharing and the other, by withholding. And yet both built lasting auras.

Virgil Abloh: The Master of Open-Source Legacy

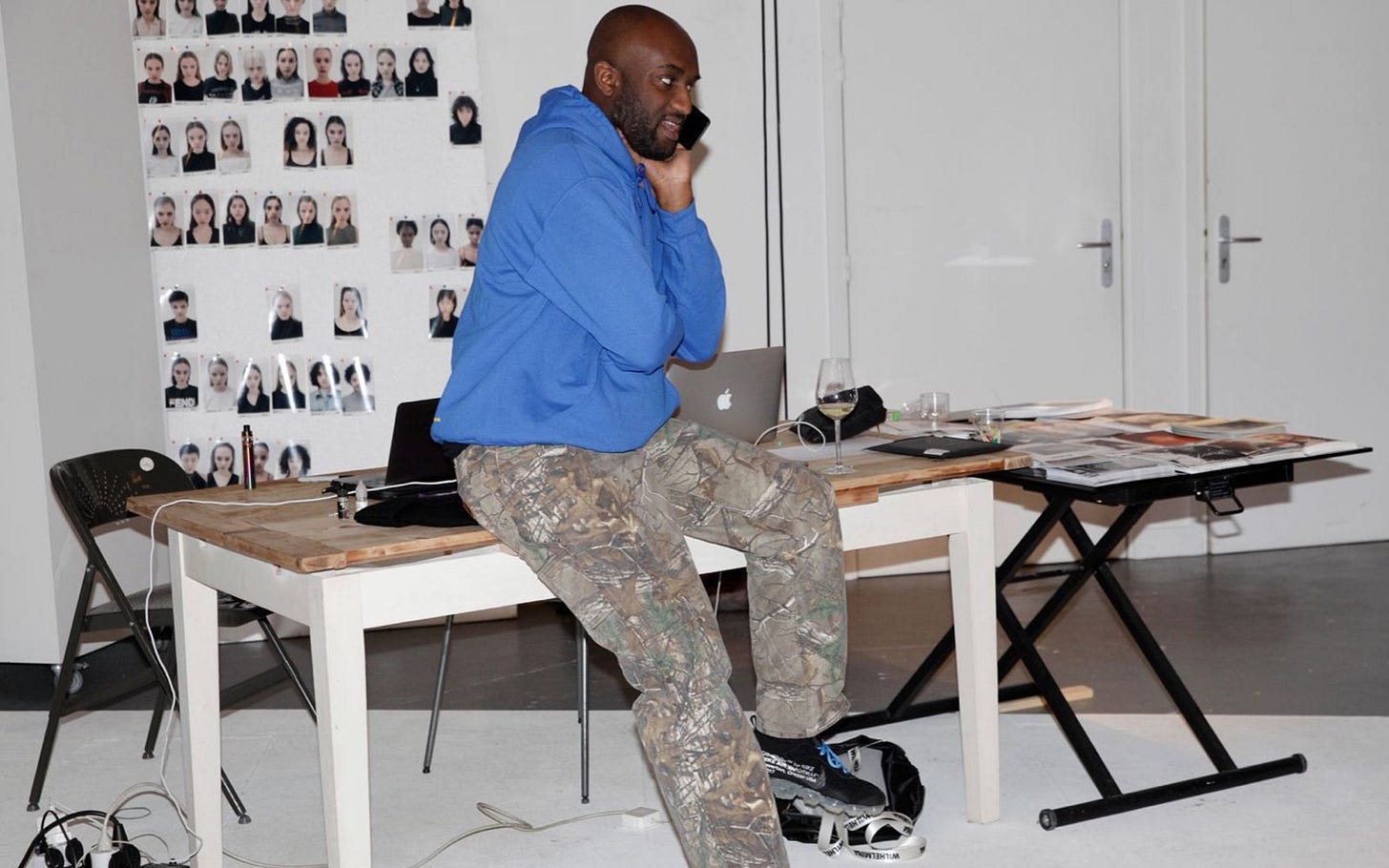

There was nothing hidden about Virgil Abloh. An architect by trade who grew to become one of the most influential and prolific designers of the modern age, he lived in the open — creatively, digitally, and culturally. Where so many before him built mystique through distance, Abloh flipped the script. He reshaped what mystique could mean for a generation raised online.

He understood that transparency wasn’t a threat to artistry. It was a tool of scale. It was intentional visibility — not self-exposure for attention sake, but self-exposure as a creative tool. He knew that the best way to distribute influence wasn’t to hoard it. It was to document it, share it and let others remix it. He turned his presence into a kind of platform and aura into something that could be taught.

Hypervisibility as Strategy

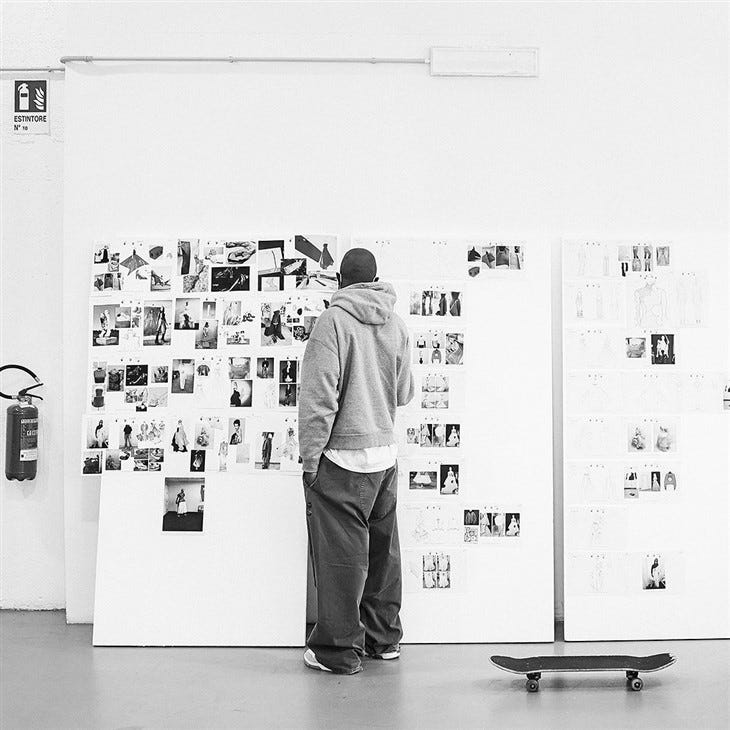

Abloh didn’t believe in mystery. If Margiela built myth through erasure, Abloh built his through open tabs and open loops. He showed you how he made things. He’d post screenshots of his process, annotate his own work and drop references in real time. His muth was built on his presence, being always online, always explaining, always inviting you BTS.

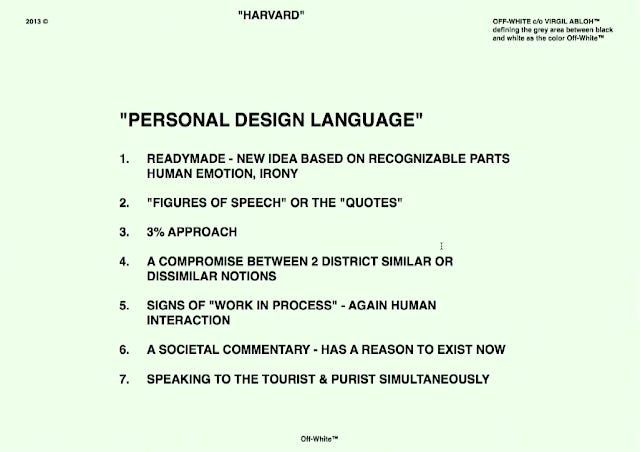

He was part designer, part DJ, part philosopher, part Tumblr kid, and he brought all of that into his work. His shows were live-streamed, he screen-printed his quotes and his inspirations were cited in Helvetica bold. He made the process fully visible, and in doing so, turned transparency into its own form of aura.

And this wasn’t a fluke of the internet era. It was the first deliberate myth of its kind: the designer as an educator and the process as art. He showed you the scaffolding — and somehow, that only made the structure feel bigger.

The Designer as Platform

What made Abloh singular wasn’t his aesthetics — it was his approach to authorship. He positioned himself as a node in a network of other talents. He quoted his influences openly — Caravaggio, Margiela, Duchamp, Kanye — all as a tool to build context.

He understood the difference between influence and imitation and used that understanding to build context. Where others feared being derivative, Abloh layered references with confidence and made them all part of the work. This transparency wasn’t naïve, it was fully tactical. He knew that crediting your sources could feel generous, and that generosity builds community. He framed himself as a collaborator, even when he was solo, and that made him bigger because people saw themselves in the work.

This kind of transparency was radical. It challenged the traditional fashion hierarchy — where reference is often buried and credit gatekept. Virgil made influence public, and in doing so, gave younger creatives permission to trace their own paths without shame. It was generosity as authorship and citation as community-building.

Brand as Ecosystem

What Abloh understood was that branding wasn’t about logos, it was about systems. His projects – whether Off-White, Pyrex Vision, or his work at Louis Vuitton – each became a hub for a larger world. They were never about single statements, instead he was selling frameworks, philosophies and aesthetic entry points, all that acted as access points to a worldview.

Each brand became an ecosystem of ideas: part blog, part label, part art school. He designed things with unfinished edges and quotation marks, with just enough space for others to enter. His genius wasn’t in a single silhouette or idea, but in the way he gave people permission to remix the work. Almost like he open-sourced the aura, left the edges unfinished and encouraged you to make it yours.

And when he died, it felt like an archive collapsed. But also like another expanded. The network that he built — not just of collaborators, but of concepts – already seeded a thousand offshoots. Ideas he pushed could live on without him and his myth could multiply, potentially forever.

Kai Althoff: The Disappearing Act

If Virgil Abloh was the myth of the always-online, post-brand artist, Kai Althoff is something closer to a pre-internet myth. He’s not prolific in the public eye, but when he does appear, it’s in the form of immersive, unsettling installations that feel like glimpses into an inner world you were never meant to access. He doesn’t explain, self-document, or self-reference. He appears when he wants to — then disappears again, leaving behind a thick, psychic residue.

His presence is sparse, but his affect is heavy. In contrast to Abloh’s everywhere-at-once distribution, Althoff's aura comes from compression. From holding it in and not giving it away.

Controlled Withdrawal

Where Abloh opened the gates, Kai Althoff quietly vanished behind them. His work appears in major institutions — MoMA, the Whitney, Documenta — and yet he remains ghostlike. Little is written about him, interviews are rare and public appearances and almost non-existent, but still, his myth is able to grow.

When he does appear, it’s never as just a painter or sculptor or performer. It’s as a world-builder. His work is messy, uncanny, often unsettling — installations full of dolls, drawings, textiles, characters. They don’t declare a message, they emanate mood.

This is not a recluse story in the slightest. Althoff isn’t hiding, he’s just curating distance. He appears when he wants, in forms that often blur the lines between installation, performance, and painting. He doesn’t explain or follow press cycles. He simply lets the work exist.

World-Building Through Obliqueness

What defines Althoff’s work isn’t medium or style — it’s obliqueness. Althoff’s work feels like your walking into someone’s memory. They are uncanny, layered and dreamlike. Dolls, mannequins, textiles, cryptic imagery. It’s not clear where the work begins and ends. He refuses clarity, and in doing so he’s able to create atmosphere.

On the contrary to Abloh, his installations feel like chapters from a story you’re not meant to fully understand. Like a diary left behind in a dream. Language sometimes appears, but it’s often cryptic, handwritten and fragmented. And this is what makes Althoff so magnetic — not clarity, but atmosphere. Similar to Margiela, there is a wanting to understand, the question, to seek answers. And when you look for them – there is nothing there. His practice creates a kind of charged space where viewers have to lean in, use intuition, fill in the blanks. It creates intimacy through ambiguity.

Aura as Absence

Althoff’s mystique is methodology. He creates intimacy by withholding. Althoff reminds us that you don’t need scale to create presence. Rather absence can become a kind of presence. It makes the work feel alive, as if it’s still unfolding without you, even when you’re gone. His aura isn’t distributed across platforms. It accumulates slowly — in rumours, in fragments, in the intensity of a single room.

He doesn’t chase visibility, yet he still haunts the art world. Critics speculate. Collectors obsess. But Althoff never clarifies, he makes work that insists on being felt, not understood. Like Dylan in interviews, or Margiela through his absence, Althoff controls his narrative by not participating in it. His work isn’t a brand — it’s an atmosphere. His myth lives in everything that remains unsaid.

And that’s where the power lies, in the refusal to explain and the generosity of ambiguity. Whether intentional or not he has built a myth by offering only fragments and letting others assemble the rest.

So what’s the takeaway?

Abloh and Althoff couldn’t be more different in method. One made presence into a distribution model. The other turned absence into a form of intimacy.

Abloh showed us how to build community through radical transparency, by sharing the scaffolding and scaling aura through openness. Althoff shows us how to build magnetism through mystery, by letting the silence shape the story and trusting the work to haunt on its own.

One created access. The other created atmosphere.

But both understood the same thing: aura is a system. It’s not just about being seen or creating distance — it’s about how you design your relationship to visibility and how you build a world that moves with or without you in the frame.

Thanks for tuning in for Part II…

We’ve looked at myth, how artists like Margeila built myth by refusing to adhere to the cult of charisma and personality. And we’ve looked at mystique vs. transparency, and how Virgil and Kai build opposing worlds, and how they spoke/speak to their audience.

We’ll now move into: Part III. Coming up we’ll look at what happens behind the aura. The habits, compulsions, and rituals that give it form. From Alex Katz to Karl Ove Knausgård, we’ll look at how creative discipline becomes its own kind of spiritual practice — and what it really takes to sustain that energy over time.

Ciao! See you there.

For Everyone (On + Offline)

Wow amazing post, thanks for sharing ✨